LULLABY

Stockholm: August 29- September 30, 2013 (extended until October 31, 2013)

Press Release:

Rock-a-bye baby, on the treetop,

When the wind blows, the cradle will rock,

When the bough breaks, the cradle will fall,

And down will come baby, cradle and all.

A familiar lullaby has the Proustian power to transport us back to childhood. In addition to nostalgically evoking a more innocent time, lullabies’ somber tunes and melancholic lyrics (often referencing loneliness, sorrow, and even death) can trigger an incongruously mature mix of feelings—from love and security, to fear and sadness. Visualizing this confluence of naïve and adult themes, the exhibition “Lullaby,” curated by Paul Frank McCabe, gathers works by Lisa Brice, Carsten Höller, Yoshimoto Nara, Pablo Picasso, and Claudette Schreuders. Rife with autobiographical undertones, the three paintings and two sculptures shown together here are reflections on childhood that reveal as much about the psychology of the adult artists as about their archetypal young subjects.

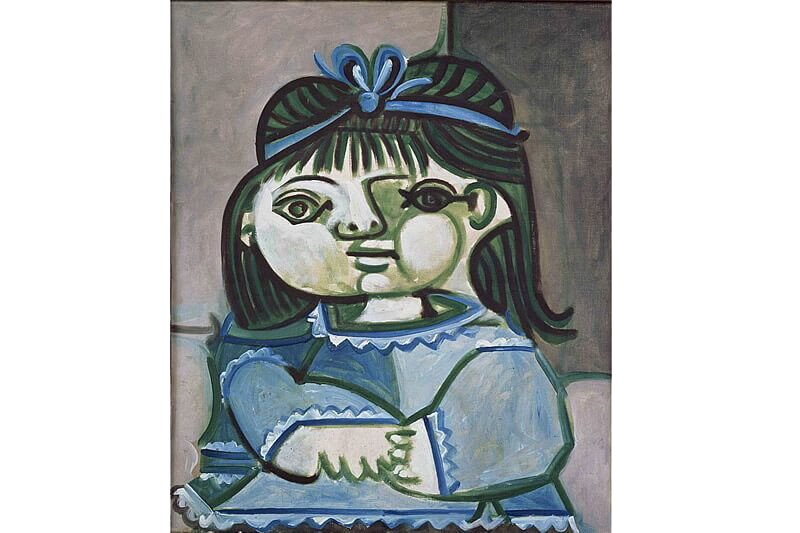

A prolific painter of children (especially his own), Pablo Picasso opted for a subdued palette of blues, grays and greens to depict Paloma, 1951—a touching portrait of his youngest daughter. Sweet details like her blue hair ribbon, round cheeks, and pudgy hands testify to the sheer delight Picasso took in rendering the two-year-old’s innocence and cuteness. However, the painting also depicts Paloma in a sophisticated manner that makes her appear wise beyond her tender age. Her wide-eyed non-smiling expression and formal pose (sitting with hands clasped over her lap), for example, reveal a poised model rather than a goofy toddler. Without being sentimental, this portrait is an ode to childhood as seen through the eyes of a doting father and a brilliant painter.

Children are recurring subjects in Yoshimoto Nara’s paintings, drawings and sculptures. The brunette girl in the painting Missing in Action, 2000, wears a pale green dress and is depicted in Nara’s signature Manga-esque style—characterized by an oversized head, large wide-set eyes, and a diminutive simplified body. Looking off to the left with an expression of indigence tinged with naughtiness, the anonymous child embodies an odd combination of cuteness and wickedness. This association of children (and by extension childhood) with both good and bad qualities is typical of Nara’s work, which is often described as “kowa kawaii” (a Japanese expression that translates roughly as “creepy cute.”) Describing his own childhood, Nara has frequently referred to the intense loneliness he experienced growing up as a latchkey kid in northern Japan. Although Missing in Action is not a self-portrait, the figure floating in an undefined background—a drab peach monochrome—without a real sense of place or any visible worldly attachments, relates directly to the artist’s personal childhood experience.

Often basing her paintings on photographs from her own childhood, Lisa Brice uses thin and drippy blues, greens, and grays to evoke distant, but psychologically potent, experiences. Garden, 2005, (whose title calls to mind the biblical scene of innocence lost) is based on a photo of the artist as a young girl in the yard of the house where she grew up. Standing alone at the center of the composition, the artist/subject looks out at the viewer from an ethereal pool of light. Although her face is too washed out to really be readable, the girl’s body language (bowed head, clasped hands, and coy contropasto pose) conveys an endearing, if slightly awkward, self-possession that is characteristic of school-age children. Two long shadows dominating the painting’s foreground approximate the viewer’s perspective both physically and psychologically. By allying the viewer with these unidentified (but undoubtedly adult) figures, Brice reminds us that the notion of innocence lost—whether this be a pleasantly nostalgic or upsettingly traumatic recollection—is contingent on a mature and worldly perspective.

Another striking self-portrait, Claudette Schreuders’s The Insider, 2009, is part of the series “Close, close,” which takes its name from a poem by Elizabeth Bishop and explores complex emotions related to pregnancy, childbirth, and motherhood. Presenting herself as an unsettling fertility figure, Schreuders’s wood effigy stands less than two feet tall and is nude except for a pair of white underwear. The sculpture’s juvenile features (diminutive size, squat body, oversized head and hands, wide eyes) establish a complicated relationship between mother-to-be and unborn child. Instead of proudly or protectively calling attention to the new life inside her swollen belly, the artist depicts herself gazing out blankly with her hands casually resting on her lower back. Like a lullaby that is simultaneously soothing and upsetting, Schreuders’s sculpture occupies a disquieting limbo—in this case one wherein maternity and childhood are encountered simultaneously.

The only non-human presence in the exhibition, Carsten Höller’s Reindeer, 2009, is a life-size polyurethane sculpture of a newborn fawn. Curled up on the floor—apparently too frail yet to stand—the young animal exudes vulnerability and cuteness, naturally triggering the viewer’s maternal instinct. Details including actual deer hooves and mesmerizing glass eyes imbue the sculpture with an uncanny realness that confounds its shocking neon green patina. Höller has created other animal sculptures including a dolphin, a hippopotamus, a crocodile, and a walrus (“Animal Group,” 2011), but his reindeer is particularly evocative of childhood nostalgia—conjuring youthful fantasies inspired by Christmas carols or Hans Christian Andersen fairytales.

Close, close all night

the lovers keep

They turn together,

in their sleep ...

MCCABE FINE ART

Noted art advisor, dealer and collector, Paul Frank McCabe, opened McCabe Fine Art in Stockholm, Sweden in 2013. An extension of his eighteen years of art market experience and connoisseurship, the beautifully renovated showroom in central Östermalm presents works by modern and contemporary masters as well as emerging talents. Through a program of curated, thematic and monographic exhibitions, McCabe Fine Art brings new voices to Scandinavia’s dynamic international art scene.

For more information, please contact us at paul@mccabefineart.com or +46 (0)709 99 77 46.